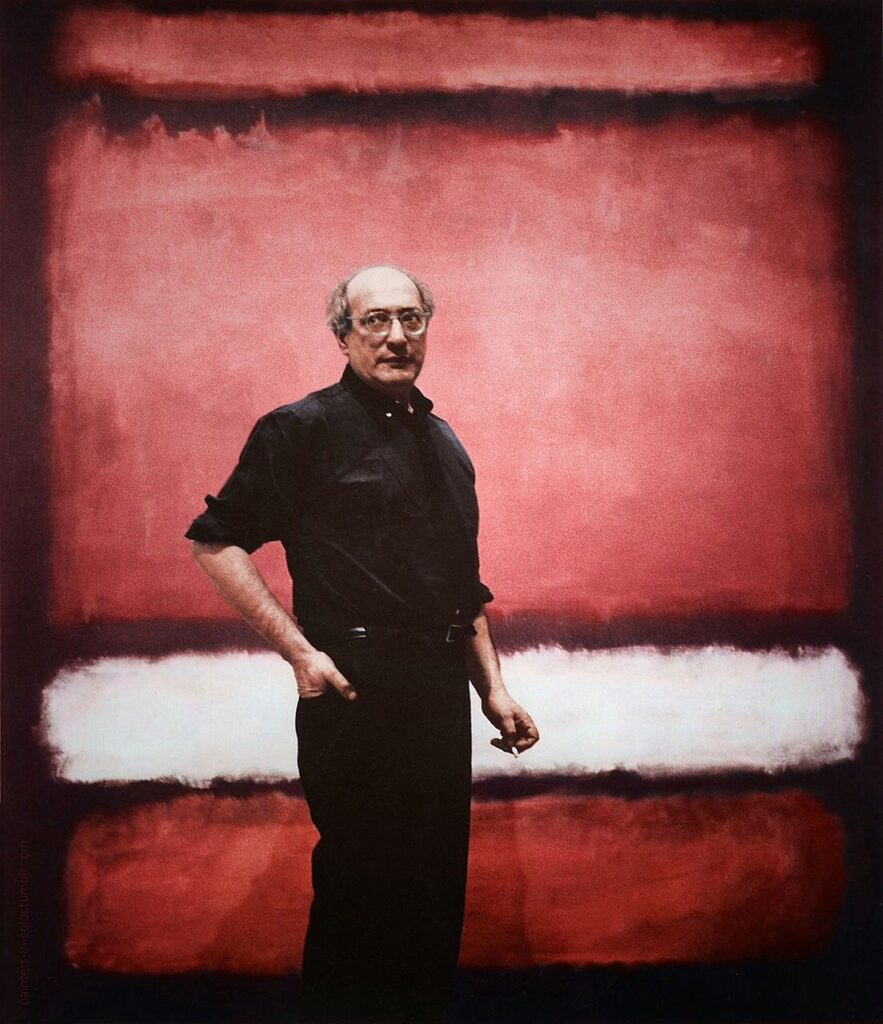

Mark Rothko: When a misunderstood artist enters his studio to splatter some of his overflowing emotions onto a canvas in an unconventional manner, what becomes his inspiration? Some would say the ‘overflowing emotions’ are enough for a man to create magnificent art. Something that evokes storms inside the viewer – why then, is he misunderstood? There is universality to emotions. One of the many fantastic facts about life is that one never goes through any emotion alone.

But what if an emotion is thrown on a canvas without any explanation? What must one make of it? It is natural to misunderstand the work at first. However, when one stands in front of such a work – with enough time in his hands to invest into the painting; they finally understands those emotions. And the inspiration behind the strong portrayal of feelings reveals itself – Music.

The Road Not Travelled

Mark Rothko (Marcus Rothkowitz) was born in 1903 in Dvinsk (modern day Daugavpils, Latvia) to an atheist family. When he was 10 years old, the Rothkowitz family moved to America to escape the growing tensions in the political climate of the Russian Empire.

The young, academically excelling Rothko later moved to New York to become a painter and befriended multiple young budding artists, one of whom was Milton Avery – a modernist painter who, with his neat and vibrant colours, had a significant impact on Rothko’s work. His vision for his work was to be placed in a room where an individual can picture himself in a meditative state while looking at his paintings.

This thought occurred to Rothko when he was commissioned to hang a bunch of his paintings in a newly opened upscale restaurant in New York. Rothko’s motive was to make the rich suffer in the room by the presence of his overwhelming paintings. However, it was not an easy task to get the attention of rich, stuck up individuals who do not see anything beyond their profit, and in this case, saw his paintings as mere decoration on the restaurant walls.

Yes, the first look at a Mark Rothko painting is always interesting. My first glance at a Rothko was, much like a conservative 19th century art critic – brief, unimpressed and even with a little detest. But that was before I sat with his work. And now that I have some understanding about the beautiful artist that he was – it is safe to say that my views have changed at last.

One needs to give time to paintings before giving their final verdict. Whether it is a busy painting of Rembrandt or a seemingly simple one of Rothko. Every art requires patience and time to allow itself to flow through the viewer — just like music.

Rothko did not choose the obvious manner of depicting anything – nature, doom, tragedy or vulnerability. And even refused to give any explanation as to what his paintings conveyed. He took another route to bring out deep, dramatic emotions within the viewer, a road that was not travelled by artists before him.

An unbelievably simple and genius approach that immediately drives monotony away and scandalizes a primitive. And he did not do all of that alone, but with the help of another genius artist known for his simple balanced perfection – Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

Mark Rothko and Mozart

“I became a painter because I wanted to raise painting to the level of poignancy of music and poetry.”

– Mark Rothko

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was born in 1756 in Salzburg, Austria. The child prodigy rose to fame at the age of 6 with his genius melodies and went on to become one of the greatest classical music composers in history. Like a stereotypical brilliant and loved artist, he died at a terribly young age of 35. Though his life was short, he left a remarkable impact on multiple lives – including Mark Rothko’s, born 147 years after him.

Mozart’s melodies remain unforgettable to this day because his music has simplicity and purity – a characteristic that is so simple yet so rare because it takes immense cultivation for an art to get there. Mozart was gifted with this understanding. He mastered balancing diatonicism (purity) and chromaticism (colour) with elegance. And it is because of this particular characteristic that his music has memorability and that his simplicity has turned into sublime.

Mozart had a direct influence on Rothko’s art. The artist would listen to Mozart while painting in an attempt to achieve that transparent and crisp style in his work. He would sit in front of his paintings for hours, visualising Mozart’s music – which we will be able to see further. Rothko had a clear vision for his paintings. He wanted nothing more for a person than to find himself in his work – he was aware that the moment of revelation would move the viewer to tears. An ability that the music of Mozart also holds.

This straightforward style of Rothko led him to seclude himself from the world as his fame grew but people repeatedly failed to visualise music through his art. He became depressed and turned to heavy drinking and smoking, and ultimately took his own life in his studio at the age of 66, before giving his paintings to London’s Tate Gallery where his art hangs in a quiet room to this day, just how he always wanted.

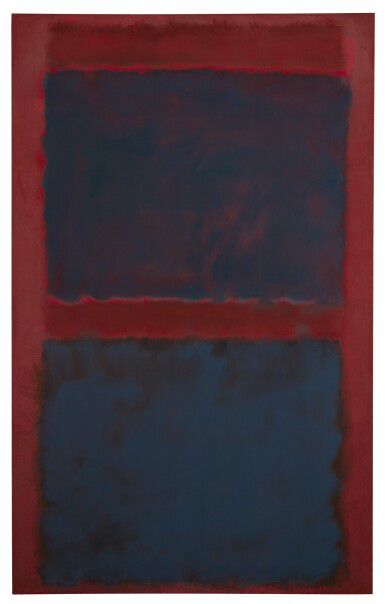

The Simple and Sublime

Taking a look at Rothko’s Untitled (Black on Maroon), what does one see? Two giant patches of black colour that turn blue-grey on a canvas that was painted entirely with maroon at first. A part of that maroon is seen in between those patches. As simple as it could be. But what is it that the eyes don’t pierce through? Rothko left his painting untitled, as his other paintings, because it could not be restricted to one name and identity.

There are two giant grey squares over maroon. Perhaps the square that is below is a reflection of the one above, and it is the deep maroon barrier that separates the two. Or perhaps it is the depiction of layered emotions painted violently yet meticulously that turn the darkness of black into grey with a blue haze, symbolising a period of transition from absolute hopelessness toward a more diluted, bargained sadness. It could portray anything.

The use of such dark colours symbolise his mental state as he was struggling with depression at the time. He gradually shifted from using lighter and vibrant shades like orange and yellow to much darker colours like black, grey, burgundy and deep blue. This shows his death on the canvas before he could physically kill himself.

In the 19th century, a Romantic painter named Caspar David Friedrich painted Monk by the Sea (1808-1810) a painting that shows the vast sky above, and the land below– on which walks a monk. What separates the two is the sea. The similarity between this painting and a Mark Rothko was drawn by Robert Rosenblum in 1961.

The painting is soothing, meditative with colours that predict a storm. The art critics of the time had a field day criticising his work. As they claimed that there was not much to see in it. The conservative art critics were used to seeing art that told a story, which they thought was lacking in this painting because it only showed nature. It was believed that this work was verging on abstraction because it provoked the viewers to think.

However, if one plays one of Mozart’s symphonies while looking at this work, the perspective elevates and widens, the chest beats with inexplicable emotions and tears roll down the cheek. Rothko’s work is similar to this particular one of Friedrich in a way that it holds the power to make one cry in awe.

The Artist’s Vision

Rothko was always clear about what he wanted to convey through his art. He was persistent throughout his life that his work should scream drama – something that was present in the music of Mozart. He wanted to achieve this through simplicity, not chaos. He dedicated his life to bringing out the most profound human emotions in the most uncomplicated manner.

In the words of Friedrich Nietzsche, “Art should dramatize the terror and struggles of existence.” something that Rothko succeeded in attaining. Though misunderstood at first, but decades later people get his message and can visualise the music through his work – completing the dream of a misunderstood painter and feeling the music in the artist’s vision.