Death of a Pope: Edward Berger’s political thriller Conclave was one of the most talked-about films at the 97th Academy Awards. Based on Robert Harris’ 2016 novel of the same name, the film follows the events that unfold after the sudden death of the Pope, leading to an intense battle of power, faith, and hidden scandals within the walls of the Vatican.

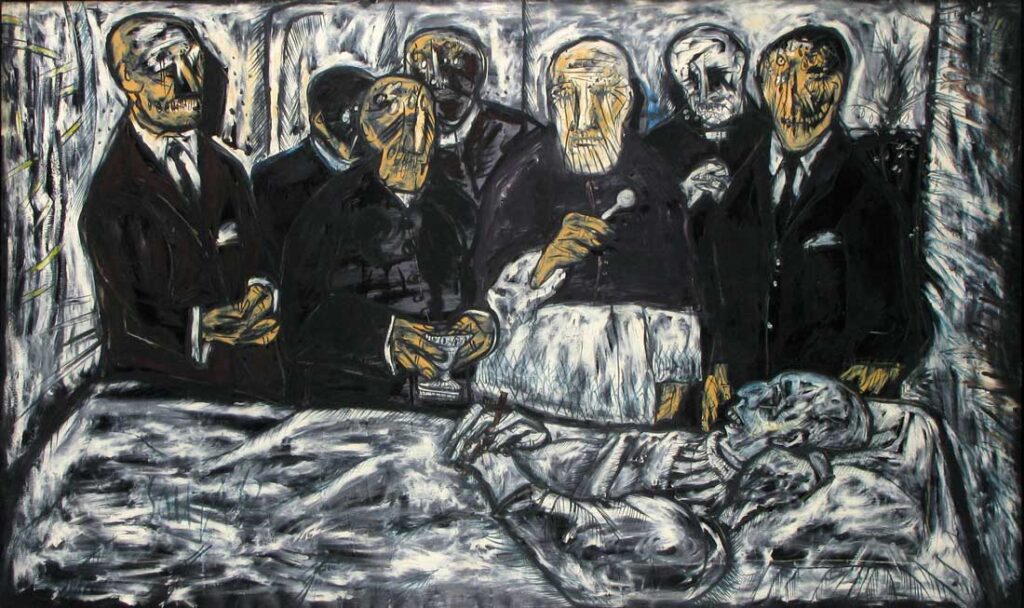

Watching this two-hour-long film took me back to a moment in November 2021, when I encountered F. N. Souza’s 1962 oil painting Death of a Pope at the Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation in Mumbai. Souza’s painting recreates a photograph of the controversial Pope Pius XII on his deathbed, surrounded by ministers performing the last rites. However, rather than offering a straightforward depiction, Souza distorts and exaggerates the scene, transforming it into a dark, grotesque, and unsettling commentary on death, power, and the paradoxes of human belief and behaviour.

Life of Souza

Francis Newton Souza (1924–2002) was one of India’s greatest modern artists. Born in Portuguese Goa in a strict Catholic household, he was raised by a single mother who wished for him to enter the priesthood. But the family later migrated to Bombay, where young Newton would go on to fiercely reject the path of organised religion.

Souza’s rebellious streak was evident early in life. He was expelled from St. Xavier’s College for creating pornographic graffiti on its walls. Later, he joined the J.J. School of Art but was also expelled for pulling down the Union Jack during the Quit India Movement—acts that reflect both his irreverence for authority and his engagement with the political currents of his time. To understand Souza’s art, one must understand the world he inhabited—particularly the political and cultural atmosphere of 1940s Bombay.

History of Bombay & the Death of a Pope

Nationalist sentiment was at its peak following the Quit India Movement, which was launched from the city in 1942. At the same time, the Communist Party of India held considerable sway over Bombay’s political life, especially among mill workers and their unions. The textile industry was booming, and where today’s skyline is marked by gleaming towers, the city once pulsed with cotton mills and the working class who sustained them. These workers, alongside a politically conscious intelligentsia of writers and artists, formed the bedrock of Bombay’s left-wing activism.

It was also a time when Jewish refugees escaping Nazi persecution found refuge in Bombay. These immigrants brought not just stories of survival but also new aesthetic sensibilities. Bombay’s artists received significant mentorship and patronage from émigré artists such as Walter Langhammer, Rudolph von Leyden, and Emmanuel Schlesinger. They introduced Western modernist idioms and helped lay the foundations for an emerging Indian modern art movement.

These influences culminated in the formation of the Progressive Artists’ Group (PAG), which made an important contribution to Indian modern art, producing artists like S. H. Raza and M. F. Husain. Souza was one of the founding members of PAG. The group sought to break free from both European realism and traditional Indian styles, creating a bold, modern visual language rooted in personal expression and political critique. It is within this context that Death of a Pope must be viewed.

Analysing the Death of a Pope Artwork

At first glance, the death of a pope painting appears sombre: a group of clergy gathers solemnly around the corpse of a pope. But closer inspection unravels this façade. The faces of the clergy are monstrous, distorted, and mask-like—twisted beyond human recognition. The Pope, lying inert in the foreground, shares the same disfigured features. The composition is claustrophobic—every inch of the canvas bristles with tense, aggressive linework that seems to close in on the viewer.

The expressions on the ministers’ faces are unreadable. Their eyes are hollow or altogether absent; their mouths are frozen in sneers or grimaces. The heavy black strokes used to render their features evoke anguish, shrewdness, and repression. These figures do not simply occupy the canvas—they accuse the viewer. They compel us to confront something darker: the play of institutional power, and the moral corruption that comes with it.

This painting by Souza has been interpreted in many ways: as an attack on the Church’s hypocrisy, a reflection of his antagonism toward the Catholic Church, or as a critique of colonialism shaped by his experience of growing up in Portuguese-ruled Goa, where Catholicism was not only a spiritual institution but a symbol of European dominance. But to reduce this work to ideological criticism alone would be reductive.

Souza’s distorted figures and violent brushstrokes are more than mere arrack—they are a projection of inner turmoil and moral tension within the system and the humans who make up the system. The painting is a window into the emotions of a corrupt world. It invites us to consider what happens in the minds of people, especially those who hold power. What masks do they wear? Or how do they behave when opportunity arrives? The Death of a Pope painting becomes a mirror held up to our own reality, where institutions sanctified by tradition may conceal rot beneath their surface, and where the human condition is laid bare in all its contradictions.

Souza once said, “Renaissance painters painted men and women, making them look like angels. I paint for angels to show them what men and women really look like.” That statement is a declaration that art must not flatter but reveal—that truth, however ugly, must not be hidden beneath beauty.

In Death of a Pope, Souza doesn’t just show us a dead man surrounded by the living. He shows us a world where the lines between virtue and vice, faith and power, life and death, are blurred beyond repair. The painting lingers in the mind, not for what it shows, but for what it dares us to confront.