Bhupen Khakhar (1934–2003), born in Bombay, was not only a celebrated Indian artist but also an accountant by profession. A prominent member of the Baroda Group of Artists, alongside luminaries like Gulam Mohammed Sheikh and K.G. Subramanyan, Khakhar contributed to an alternative vision of Indian nationalism that diverged from the traditions of the Santiniketan and Bengal schools.

Self-taught as an artist, Bhupen Khakhar’s career began relatively late in life. His oeuvre is deeply figurative, often exploring themes of the human body and identity, making him a unique voice in modern Indian art.

Like many queer men in India, Bhupen Khakhar remained closeted for much of his early life. However, in the post-1980s, his queerness became a central theme in his work, with pieces that boldly embraced his sexuality. Although Indian critics were initially reluctant to engage with the queer subtext in his art, Bhupen Khakhar’s pivotal work “Two Men in Benares” brought his identity to the forefront. It was British art critic Timothy Hyman who explicitly acknowledged Khakhar’s sexuality as integral to his artistic narrative, referring to his series of works from the 1980s as “The Coming Out Paintings.” This collection includes masterpieces such as “You Can’t Please All” (1981), “Two Men in Benares” (1982), and “Yayati” (1987).

You Can’t Please All: Layers of Narrative and Self-Reflection

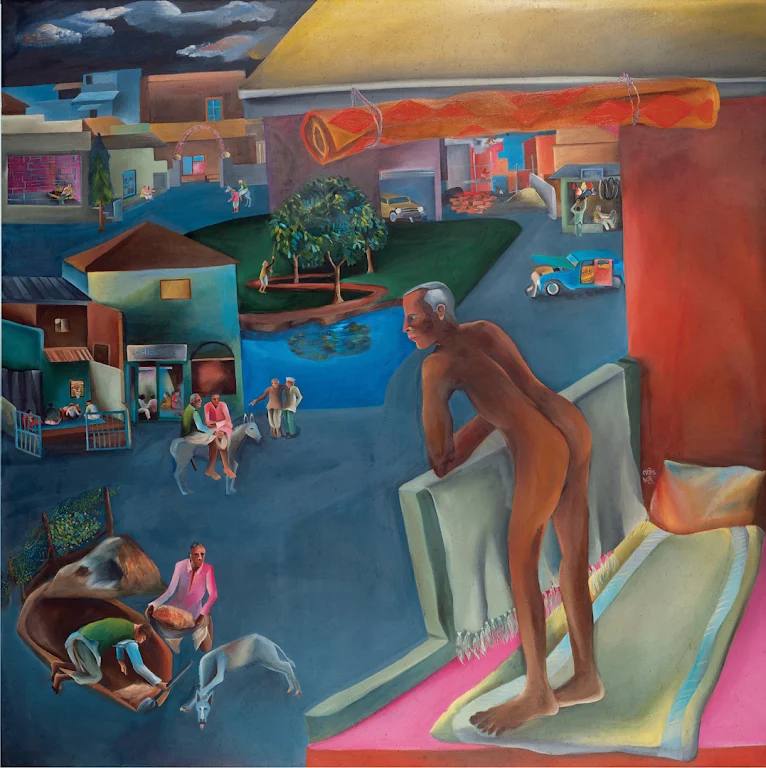

Bhupen Khakhar’s You Can’t Please All (1981) is a striking example of his ability to weave personal vulnerability into a richly detailed visual narrative. The painting captures a deeply autobiographical moment while reflecting on broader human experiences, making it both intimate and universal.

The composition centers on a nude, elderly man—Bhupen Khakhar himself—standing on a balcony. His bare body is presented unapologetically to the viewer, while the onlookers within the painting only see a man without a shirt. This distinction between what the viewer perceives and what the characters in the painting see is crucial. For us, the figure’s nudity represents complete exposure, symbolizing Bhupen Khakhar’s emotional and sexual vulnerability. It is a daring act of self-representation, especially in 1980s India, where discussions around queerness and male nudity in art were largely taboo.

The balcony serves as a symbolic threshold between Khakhar and the world. It is both a stage and a barrier—where he reveals himself to the viewer yet remains distanced from the judgment of those in the painted scene. This duality mirrors Khakhar’s own life: as a queer man, he navigated the tension between societal expectations and his true identity. The balcony’s physical separateness emphasizes his isolation while simultaneously creating a platform for his declaration of self.

The backdrop of the painting is alive with everyday activities, seamlessly transforming a seemingly ordinary setting into a richly layered narrative. It features a man reaching for mangoes from a tree, another engrossed in repairing his car, construction workers diligently toiling in the background, and a father and son leading their donkeys. Amidst these scenes, two figures stand out, pointing and appearing to mock the father-son duo and their donkeys, adding a layer of tension and commentary to the otherwise mundane tableau.

These interconnected scenes create a tapestry of life, blending the ordinary with the metaphorical. At the heart of the narrative is the story of a dead donkey, lying lifeless after being beaten by its owners. The mocking gestures of the two bystanders underscore the cruelty and judgment faced by the donkey—an apt metaphor for societal condemnation.

On the far-left corner of the painting, Bhupen Khakhar includes a grave dug for the donkey, lending a sense of closure and inevitability to its plight. This story parallels Khakhar’s personal journey, where the title You Can’t Please All resonates deeply. It suggests the impossibility of conforming to societal expectations while remaining true to oneself. For Khakhar, the donkey’s fate mirrors the judgment he faced as a queer man in a conservative society.

In a culture where self-portraiture often avoided vulnerability, Khakhar’s choice to depict himself nude was groundbreaking. He subverts traditional norms of representation, particularly in Indian art, where the subject is typically external and idealized. By placing himself at the center, Khakhar confronts themes of shame, desire, and identity. His nudity is not sexualized but instead a statement of honesty and defiance—a radical act of “coming out” in a society unprepared to accept such openness.

The title “You Can’t Please All” operates on multiple levels. It critiques the futile pursuit of societal approval, highlighting the hypocrisy and cruelty of collective judgment. The title also reflects Khakhar’s acceptance of his own identity as a queer man and his rejection of societal expectations that sought to confine him. It challenges the viewer to reflect on their own judgments, inviting empathy and self-awareness.

Bhupen Khakhar’s storytelling prowess shines through in this work. In an interview with Thames Television’s Afternoon Plus, he expressed his desire for viewers to engage with the narrative aspect of his art. In You Can’t Please All, the everyday activities depicted are not random; they collectively build a story that complements the central theme of vulnerability and societal critique. The painting invites viewers to delve beyond the visual to uncover its layered meanings, making it an intensely personal yet universally relatable piece.

Stylistically, You Can’t Please All exemplifies Khakhar’s distinctive approach, blending Western influences with a uniquely Indian sensibility. While inspired by the Pop Art movement, Khakhar diverged from its focus on mass media and consumer culture. Instead, he painted scenes drawn from his lived experiences, capturing the vibrancy and complexity of Indian middle-class life.

The use of bright, flat colors and detailed figures reflects Khakhar’s deep engagement with everyday realities. His satirical yet empathetic portrayal of the characters underscores his ability to observe and critique societal behaviors without losing his connection to them.

In You Can’t Please All, Bhupen Khakhar achieves a masterful balance between personal revelation and social commentary. The painting’s layers of narrative, symbolism, and self-reflection make it a timeless exploration of identity, courage, and the human condition. It stands as a testament to Bhupen Khakhar’s brilliance as a storyteller and his bravery as an artist.

Everyday Life through the Lens of Pop

Bhupen Khakhar’s depiction of the mundane is a hallmark of his work. In You Can’t Please All, he intricately captures a vibrant tableau of daily life: a man reaching for mangoes, another repairing a car, construction in the background, and a father-son duo leading donkeys. These ordinary moments coexist with the painting’s central drama, grounding the narrative in an Indian context while inviting reflection on universal human experiences.

As India’s first recognized pop artist, Khakhar redefined the genre by infusing Western influences with local sensibilities. Unlike his Western contemporaries, whose works often referenced mass media and consumer culture, Khakhar drew inspiration from the rhythms of Indian middle-class life. Despite his disdain for their aesthetic—particularly in home decor and fashion—this demographic became a central subject of his art. His nuanced critique of middle-class values reflects a love-hate relationship, offering both satire and empathy.

Khakhar’s exposure to British pop art during his visits to England shaped his practice. He admired the polished presentation of exhibitions and the consumer-driven art market, contrasting it with India’s then-nascent art infrastructure. Yet, his interpretation of pop remained rooted in his cultural milieu. Art critic Geeta Kapur aptly noted that Khakhar’s wit and sharp perceptions distinguished him from the innocence associated with Western pop artists. His art, while playful and satirical, was deeply introspective and profoundly personal.

Bhupen Khakhar’s work transcends the boundaries of genre and identity. By intertwining personal narratives with broader cultural and social commentaries, he carved a distinct space for himself in the history of modern Indian art. His brave exploration of queerness, set against the backdrop of a conservative society, and his innovative take on pop art continue to inspire and challenge viewers today.